How to Get Rich in the 21st Century | (News and Research 369)

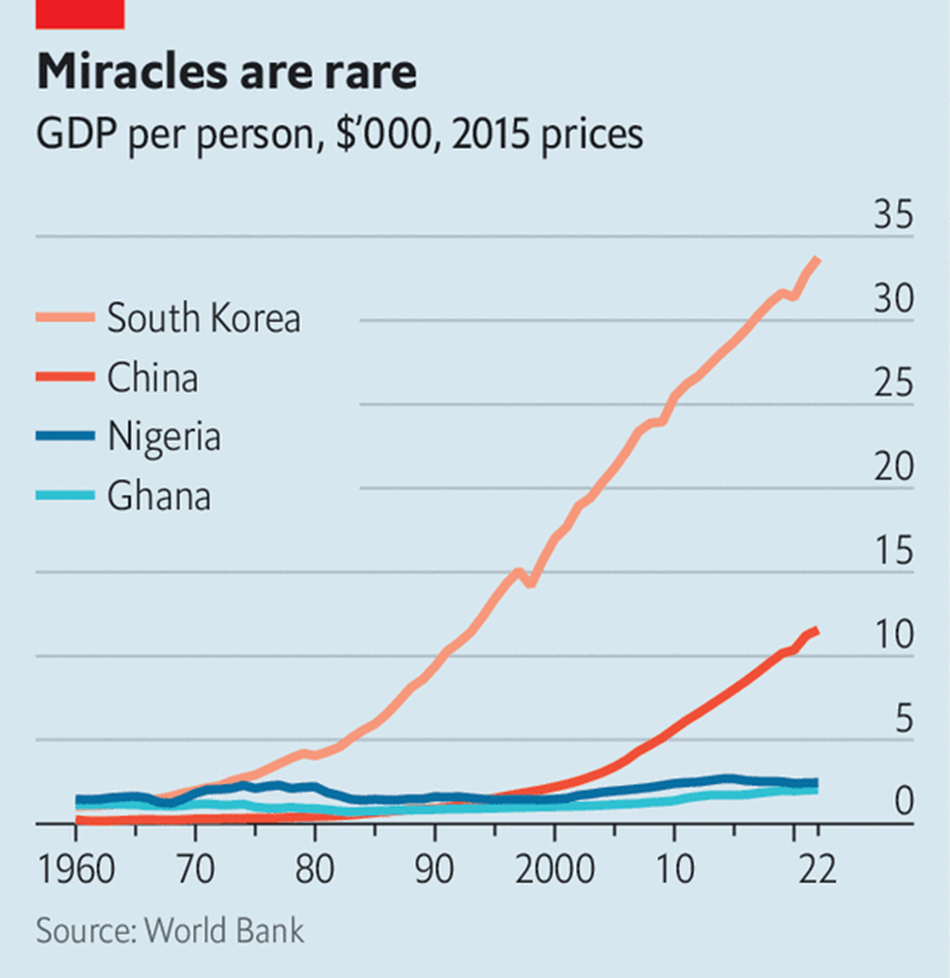

How to get rich in the 21st century | The Economist | “Qatar is building Education City, a campus that will cost $6.5bn and sprawl across 1,500 hectares, working a bit like an industrial park for universities, with the outposts of ten, including Northwestern and University College London”… and the East Asian miracle:

COVID-19 and Human Capital at the Allied Social Sciences Association Annual Meetings 2024, San Antonio | January 7, 2024, hosted by American Economic Association | Chair: Harry Patrinos, World Bank. Papers:

Covid-19 Learning Loss and Recovery: Panel Data Evidence from India (Abhijeet Singh, Stockholm School of Economics; Karthik Muralidharan, University of California-San Diego; Mauricio Romero, Mexico Autonomous Institute of Technology) Using a panel survey of 19,000 primary-school-aged children in rural Tamil Nadu, India, learning loss after COVID-19-induced school closures, and the pace of recovery after schools reopened, is studied. Students tested in 2021 (18 months after school closures) displayed learning deficits of 0.73 standard deviations (SD) in math and 0.34 SD in language compared to identically-aged students in the same villages in 2019. Two-thirds of this deficit was made up within 6 months after schools reopened. Further, while learning loss was regressive, recovery was progressive. A government-run after-school remediation program contributed 24% of the cohort-level recovery, likely aiding the progressive recovery.

Forgone and Forgotten Learning: COVID-Related Learning Losses from National Assessments in Bangladesh (Sharnic Djaker, New York University; Shwetlana Sabarwal, World Bank; Shrihari Ramachandra, International Monetary Fund; Andres Yi Chang, World Bank; Noam Angrist, University of Oxford) School closures during COVID-19 resulted in large learning losses. How much of these losses were: “forgone” learning or new learning that did not happen vis-à-vis “forgotten” learning or the deterioration of skills previously acquired? This distinction has not been made in most learning loss studies but has significant policy implications for learning recovery strategies. Using novel data from Bangladesh with comparable student test scores over time and across cohorts and grades to estimate learning losses in a way that allows us to decompose them into learning foregone vs. learning forgotten shows that overall, 17 months of school closures led to 25.2 months of learning lost. While nearly 70% of these losses were foregone learning, up to 30% were forgotten.

An Analysis of COVID-19 Student Learning Loss (Harry Patrinos, World Bank; Emiliana Vegas, Harvard University; Rohan Carter-Rau, Brookings Institution) A review of recorded learning loss evidence documented since the beginning of the school closures finds evidence of learning loss. In 36 identified robust studies, the majority identified learning losses that amount to, on average, 0.17 of a SD, equivalent to roughly a one-half school year’s worth of learning. This confirms that learning loss is real and significant and has continued to grow after the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most studies observed increases in inequality where certain demographics of students experienced more significant learning losses than others. The longer the schools remained closed, the greater were the learning losses. For the 19 countries for which there are robust learning loss data, average school closures were 15 weeks, leading to average learning losses of 0.18 SD. Put another way, for every week that schools were closed, learning declined by an average of 0.01 SD.

Are Education Innovations Tested during COVID-19 Still Relevant After? Evidence from Five Randomized Trials (Noam Angrist, University of Oxford; Claire Cullen, Youth Impact; Janica Magat, Youth Impact) Results from large-scale randomized trials evaluating the provision of education in emergency settings across 5 countries: India, Kenya, Nepal, Philippines, and Uganda, are used to test multiple scalable models of remote instruction for primary school children during COVID-19, which disrupted education for over 1 billion schoolchildren worldwide. Despite heterogeneous contexts, results show that the effectiveness of phone call tutorials can scale across contexts. There are consistently large and robust effect sizes on learning, with average effects of 0.30-0.35 standard deviations. These effects are highly cost-effective, delivering up to four years of high-quality instruction per $100 spent, ranking in the top percentile of education programs and policies. In a subset of trials, the intervention was provided by NGO instructors or government teachers and results show similar effects.

Evaluation of Educational Loss in Europe and Central Asia (Harry Patrinos, World Bank; Maciej Jakubowski, University of Warsaw; Tomasz Gajderowicz, University of Warsaw) A pre-registered analysis of the first international assessment to be published since the pandemic is conducted to estimate the impact of COVID-19 on student reading. The effect of closures on achievement is modeled by predicting the deviation of the most recent results from a linear trend in reading achievement using data from all rounds using data from 28 countries in Europe and Central Asia. Reading scores declined by an average of 20% of a SD, equivalent to just less than a year of schooling. Losses are significantly larger for students in schools that faced relatively longer closures. There are no significant differences by sex, but lower-achieving students experience larger losses.

Discussants: Tahir Andrabi, Pomona College and Michela Carlana, Harvard University

Using Education Technology to Improve K-12 Student Learning in East Asia Pacific: Promises and Limitations | Yarrow, Abbey, Shen, Alyono | Global and regional data show that it is possible to use EdTech to improve student learning. Broadcast/dual teacher model often supports student learning gains, while other approaches, including assistive EdTech, show promise.

What is the fairest and most efficient way to improve not just access to education, but outcomes too? What is the fairest and most efficient way to improve not just access to education, but outcomes too? Should policymakers focus on a broader markets and systems approach to education reform? In this episode of VoxDevTalks, Emiliana Vegas and Asim Khwaja tell Tim Phillips about what a markets and systems approach to delivering education reform is, and what it has already achieved in Pakistan and Chile.

Global evidence on the economic effects of disease suppression during COVID-19 | Rothwell, Cojocaru, Srinivasan, Kim | Governments around the world attempted to suppress the spread of COVID-19 using restrictions on social and economic activity. This study presents the first global analysis of job and income losses associated with those restrictions, using Gallup World Poll data from321,000 randomly selected adults in 117 countries from July 2020 to March 2021. Nearly half of the world’s adult population lost income because of COVID-19, according to our estimates, and this outcome and related measures of economic harm—such as income loss—are strongly associated with lower subjective well-being, financial hardship, and self-reported loss of subjective well-being. Our primary analysis uses a multilevel model with country and month-year levels, so we can simultaneously test for significant associations between both individual demographic predictors of harm and time-varying country-level predictors. We find that an increase of one-standard deviation in policy stringency, averaged up to the time of the survey date, predicts a 0.37 std increase in an index of economic harm (95% CI 0.24–0.51)and a 14.2 percentage point (95% CI 8.3–20.1 ppt) increase in the share of workers experiencing job loss. Similar effect sizes are found comparing stringency levels between top and bottom-quintile countries. Workers with lower-socioeconomic status—measured by within-country income rank or education—were much more likely to report harm linked to the pandemic than those with tertiary education or relatively high incomes. The gradient between harm and stringency is much steeper for workers at the bottom quintiles of the household income distribution than it is for those at the top, which we show with interaction models. Socioeconomic status is unrelated to harm where stringency is low, but highly and negatively associated with harm where it is high. Our detailed policy analysis reveals that school closings, stay-at-home orders, and other economic restrictions were strongly associated with economic harm, but other non-pharmaceutical interventions—such as contact tracing, mass testing, and protections for the elderly were not.