The Return on Investing in Education | (News and Research 363)

Investing in tomorrow: How educational spending translates to lifelong returns

Published on Education for Global Development

What investment can you make that will almost guarantee that you will beat the stock market?

Each year of education for a person yields approximately a 10% rise in annual earnings, outpacing returns from the stock market. This consistent 10% yearly increase persisted even amid the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, beyond the individual graduate’s earnings, society at large reaps the benefits of a more educated nation. Countries can do a lot to help, starting with ensuring that all children have access to a quality education from pre-school onwards.

Investment or expenditure?

Education, recognized as a fundamental human right according to various international declarations, serves as an essential human service. Across the globe, nations ensure a minimum standard of education, a tradition upheld for centuries. Individuals and families invest in education, as do employers and governments. In fact, most countries allocate 3-5% of their GDP and 10-20% of government expenditure to education, as indicated by Education Finance Watch 2023.

Beyond its inherent value, education also brings economic benefits. David Deming highlights the positive returns on investment in education, noting that one-third of the variation in income is due to education. He goes on to highlight the importance of investing in young children (as do many others including Heckman), but also for young adults.

The substantial economic return generated by education appears to be causal. Carolina Arteaga shows that human capital plays an important role in the determination of wages and rejects a pure signaling model. That is, it is the quality of education that determines wages, not the diploma without quality. She demonstrates this by citing a reform at a top university in Colombia that reduced the amount of coursework required to earn degrees, which led to a subsequent substantial decrease in wages.

Social benefits

Education holds a significance beyond the financial returns it offers to students; it extends far beyond monetary gains…More

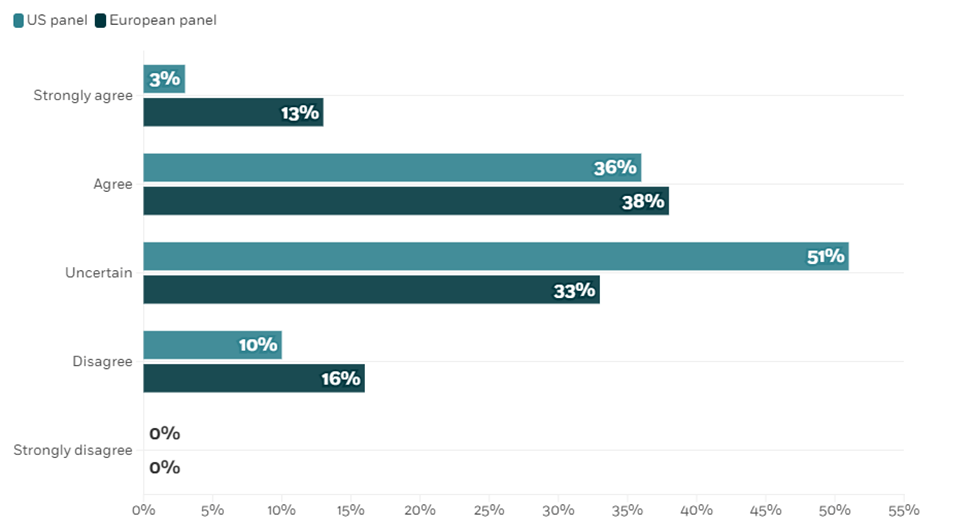

How Will A.I. Change the Labor Market? | Rapid improvements in artificial intelligence, especially generative A.I. such as ChatGPT, have given rise to concerns about the broad set of jobs that could be fully or partially automated in the foreseeable future. Will the technology lead to widespread displacement of white-collar workers and fewer opportunities for the highly educated? Could it lead to the aggravation of existing issues with income inequality? Chicago Booth’s Kent A. Clark Center for Global Markets turned to its US and European panels of economic experts for insights…eg: Use of artificial intelligence over the next ten years is likely to have a measurable impact in increasing income inequality (responses weighted by each panelist’s confidence

Daron Acemoglu, MIT: “While it is possible for generative A.I. to be a useful tool for noncollege workers, I do not see the current path achieving this, and the existing evidence is more consistent with most of the burden of displacement falling on less-educated, lower-wage workers.” Response: Agree

The returns to education and role of overeducation: an empirical analysis using panel data from Ukraine | Brintseva | The growing impact of human capital and education on economic development is leading to an increase in the returns to education in most Eastern and Central European countries. Empirical findings based on Ukrainian panel data show that returns to education have been rising in Ukraine from 8.7% in 2012 to 7.8% in 2016 and to 9.2% in 2020 for each additional year of education. Among numerous factors, complete higher education, large enterprise size, and residence in the capital have the most beneficial impact on wages. The study also analyzed which professional groups are characterized by the phenomenon of overeducation.

Hidden schooling: endogenous measurement error and bias in education and labor market experience | Kennedy | Since 1980, 25% of US students repeated a grade during their academic career. Despite this, few economists account for retention when measuring education and experience, causing bias when retention is correlated with other regressors of interest. Rising minimum dropout ages since 1960 have increased retention, causing positive bias in 2SLS estimates of the returns to education. Retention also causes endogenous measurement error in potential experience. In addition to distorting experience-wage profiles across countries, this endogenous measurement error causes the residual Black-White wage gap and the returns to a high school diploma to be overstated. Proxying for age instead of potential experience reduces this bias, suggesting age, not potential experience, should be a standard control variable.

The Return on Investing in a College Education | Vandenbroucke | The costs and benefits of a college education—tuition and higher earnings—can be thought of as if they were the price and payoff of a financial asset. In the United States, tuition costs have risen sharply and outpaced inflation in recent decades. However, the difference in earnings between workers with and workers without college also grew. Estimates of the returns on investing in a college education appear to be significant. In 2020, they ranged from 13.5% to 35.9% across six demographic groups.

A data set of comparable estimates of the private rate of return to schooling in the world, 1970–2014 | Montenegro, Patrinos | Young people experience lower employment, income and participation rates, as well as higher unemployment, compared to adults. Theory predicts that people respond to labor market information. For more than 50 years, researchers have reported on the patterns of estimated returns to schooling across economies, but the estimates are usually based on compilations of studies that may not be strictly comparable. The authors create a dataset of comparable estimates of the returns to education. The data set on private returns to education includes estimates for 142 economies from 1970 to 2014 using 853 harmonized household surveys. This effort holds the constant definition of the dependent variable, the set of controls, sample definition and the estimation method for all surveys. The authors estimate an average private rate of return to schooling of 10%. This provides a reasonable estimate of the returns to education and should be useful for a variety of empirical work, including critical information for youth. This is the first attempt to bring together surveys from so many countries to create a global data set on the returns to education. (Montenegro, C.E. and Patrinos, H.A. (2023), “A data set of comparable estimates of the private rate of return to schooling in the world, 1970–2014”, International Journal of Manpower 44(6): 1248-1268.) Working Paper Version. (see also.)

3 Comments